The four functors of Grothendieck in examples

Tuesday, May 01st, 2012 | Author: Konrad Voelkel

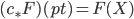

This post will discuss the definition of the four functors "pushforward"  , "pullback"

, "pullback"  , "pushforward with compact support"

, "pushforward with compact support"  and "exceptional pullback"

and "exceptional pullback"  of sheaves of abelian groups, associated to a continuous morphism

of sheaves of abelian groups, associated to a continuous morphism  of topological spaces

of topological spaces  and

and  . Then we will look at maps

. Then we will look at maps  which are open immersions or closed immersions, and calculate in the example of

which are open immersions or closed immersions, and calculate in the example of  and its closed complement

and its closed complement  exactly what happens. This is intended to give some intuition what the general four functor calculus is about.

exactly what happens. This is intended to give some intuition what the general four functor calculus is about.

The four functor formalism arises as part of the six functor formalism (add Hom and Tensor to make it six) in certain (co)homological set-ups. Where I encountered it first was in a paper I tried to read, about the stable motivic homotopy category, but most likely you'll see this stuff in papers dealing with perverse sheaves or motives and their realisations.

Disclaimer: We'll stay in the topological category for this post, i.e. the objects are topological spaces and the morphisms continuous maps. Sheaves are ordinary sheaves of abelian groups (no fancy Grothendieck topology necessary here), not  -modules of some sort. However, the discussion doesn't change too much if you translate into the algebraic category, so this should be a good exercise for the bored reader.

-modules of some sort. However, the discussion doesn't change too much if you translate into the algebraic category, so this should be a good exercise for the bored reader.

Pushforward

Pushforward of sheaves is straightforward: given a space  , a sheaf

, a sheaf  on

on  and a continuous map

and a continuous map  , the sheaf

, the sheaf  on

on  should be a sheaf that does on open subsets

should be a sheaf that does on open subsets  what

what  had done on the corresponding open subsets of

had done on the corresponding open subsets of  , i.e.

, i.e.  . Check that this definition gives again a sheaf. Observe that the constant map

. Check that this definition gives again a sheaf. Observe that the constant map  yields

yields  , so

, so  is almost the global section functor and we should think of any

is almost the global section functor and we should think of any  as some kind of generalized global section functor.

as some kind of generalized global section functor.

Pullback

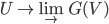

I want to define the pullback functor  as the left adjoint to

as the left adjoint to  . Of course, I have to show existence.

. Of course, I have to show existence.

If  would be an open embedding, we would have

would be an open embedding, we would have  open in

open in  for all open subsets

for all open subsets  of

of  , and it would be natural to define

, and it would be natural to define  . To see that we indeed have a left adjoint by this definition is up to you, but it fails for a general

. To see that we indeed have a left adjoint by this definition is up to you, but it fails for a general  , since

, since  needn't be open in general.

needn't be open in general.

So, given a sheaf  on

on  I define a new presheaf on

I define a new presheaf on  by

by  , where the limit ranges over all open subsets

, where the limit ranges over all open subsets  such that

such that  contains

contains  . By this "trick" we circumvent the given problem (and introduce new behaviour) and it turns out that this is a correct definition, in the technical sense that we really have found a left adjoint to

. By this "trick" we circumvent the given problem (and introduce new behaviour) and it turns out that this is a correct definition, in the technical sense that we really have found a left adjoint to  .

.

Proof of the adjunction  :

:

for an open subset  of

of  , a homomorphism from

, a homomorphism from  to

to  is just a homomorphism from

is just a homomorphism from  to

to  and a homomorphism from

and a homomorphism from  to

to  is just a homomorphism from

is just a homomorphism from  to

to  . So you see, if we have homomorphisms

. So you see, if we have homomorphisms  for all

for all  , this gives in the limit homomorphisms

, this gives in the limit homomorphisms  .

.

For the other direction, observe that if we have homomorphisms  for all

for all  , we certainly have this for all

, we certainly have this for all  , where the limit is just

, where the limit is just  , i.e. where we have just

, i.e. where we have just  .

.

Pushforward with compact support

We have already seen how pushforward generalizes global sections. As global sections give (as derived functor) cohomology of sheaves, there is a global section with compact support functor, which gives cohomology with compact support. For the locally constant sheaf  this gives back "singular" cohomology with compact support, as it appears in Poincaré duality. I will explain this in some more detail now, although I won't explain how to move from global sections to cohomology.

this gives back "singular" cohomology with compact support, as it appears in Poincaré duality. I will explain this in some more detail now, although I won't explain how to move from global sections to cohomology.

Poincaré duality states, for a smooth compact complex n-dimensional manifold X

and if X is not compact, there is still Poincaré duality:

where

is the cohomology with compact support,

is the cohomology with compact support,which is related to the functor of global sections with compact support,

just as ordinary cohomology is related to the ordinary global section functor.

The functor of global sections with compact support  is defined as

is defined as

By analogy, we define the pushforward with compact support  as a subfunctor of

as a subfunctor of  (which just means that

(which just means that  will be a subsheaf of

will be a subsheaf of  for every

for every  , which in turn just means that

, which in turn just means that  is a subset of

is a subset of  for every open set

for every open set  ).

).

This really gives a sheaf and for

the constant map to a point,

the constant map to a point,the values are exactly

.

.

An example:

Let  be an open embedding

be an open embedding  , then

, then  is just the "extension by zero", i.e. the stalks at all points of

is just the "extension by zero", i.e. the stalks at all points of  are just the same as those of

are just the same as those of  , and all other/new stalks (over

, and all other/new stalks (over  ) are plain

) are plain  .

.

Another example:

Let  be a proper map

be a proper map  , then

, then  , as you can see from the definition.

, as you can see from the definition.

A comprehensive example:

If  can be factored into

can be factored into  with

with  an open embedding and

an open embedding and  proper, we have

proper, we have  , which gives a very explicit description of

, which gives a very explicit description of  .

.

Exceptional inverse image

We define a functor  called

called  , if it exists. We should say straightforward, that it doesn't exists, in general, on the level of sheaves and this is one of the things that makes working with complexes of sheaves necessary (in fact, the derived category).

, if it exists. We should say straightforward, that it doesn't exists, in general, on the level of sheaves and this is one of the things that makes working with complexes of sheaves necessary (in fact, the derived category).

However, for innocent maps  , we can actually define a functor that is right adjoint to

, we can actually define a functor that is right adjoint to  and thus deserves to be called

and thus deserves to be called  .

.

For f an open embedding  , we have just

, we have just  , i.e. the functor

, i.e. the functor  is the left adjoint to

is the left adjoint to  and also the right adjoint to

and also the right adjoint to  .

.

The proof is similar to the proof of the adjointness of  with

with  , so I leave it out.

, so I leave it out.

Now I want to make clear why a right adjoint to  doesn't exist (on the level of sheaves) in general, for categorical reasons.

doesn't exist (on the level of sheaves) in general, for categorical reasons.

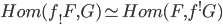

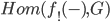

Every left adjoint functor preserves colimits, since an adjunction like

means that one can compute

as the Hom-functor

as the Hom-functor  , where colimits in the first argument are obviously preserved (now apply Yoneda lemma). There we use that the Hom-functor turns colimits in its first argument into limits, which doesn't work with limits, so left adjoints needn't preserve limits. Exercise: apply the same reasoning to see that right adjoints preserve limits.

, where colimits in the first argument are obviously preserved (now apply Yoneda lemma). There we use that the Hom-functor turns colimits in its first argument into limits, which doesn't work with limits, so left adjoints needn't preserve limits. Exercise: apply the same reasoning to see that right adjoints preserve limits.

Now being right-exact is a special case of preserving colimits, since it means to preserve cokernels (which are special colimits). Clearly,  is not right-exact, since it has cohomology: let

is not right-exact, since it has cohomology: let  be a compact space and

be a compact space and  the constant map to a point. Then for

the constant map to a point. Then for  to be right-exact, the cohomology on

to be right-exact, the cohomology on  must vanish.

must vanish.

The salvation consists of enlarging the category of sheaves to the category of chain complexes of sheaves, only to make it smaller again by introducing the appropriate definition of morphisms, which in the end gives what is called the  exists.

exists.

Concrete examples for four functors

Let us look at the embedding  and its closed complement

and its closed complement  .

.

First we will look at a skyscraper sheaf on  with stalk some abelian group

with stalk some abelian group  over

over  . We denote the skyscraper sheaf by

. We denote the skyscraper sheaf by  . By definition, we have

. By definition, we have  a skyscraper sheaf with stalk

a skyscraper sheaf with stalk  over

over  . Now

. Now  , since

, since  throws away all information from the stalk over

throws away all information from the stalk over  .

.

Okay, let's look at a local system on  , i.e. a locally constant sheaf

, i.e. a locally constant sheaf  .

.

This is the same data (an equivalent category) as the monodromy representation of the fundamental group, in this case  .

.

We have as  a sheaf with stalks just

a sheaf with stalks just  where

where  , and

, and  , since every section with compact support is away from an arbitrarily small ball around the origin.

, since every section with compact support is away from an arbitrarily small ball around the origin.

The sheaf  has the same stalks

has the same stalks  where

where  but it has a new one at the origin, given by the usual stalk-limit-formula you would write down - and in general, this is non-zero.

but it has a new one at the origin, given by the usual stalk-limit-formula you would write down - and in general, this is non-zero.

Cleary  vanishes, since

vanishes, since  picks the stalk at the origin and throws away everything else. Of course,

picks the stalk at the origin and throws away everything else. Of course,  contains exactly the "new" stalk which might be interesting.

contains exactly the "new" stalk which might be interesting.

Thinking about it, the sheaves  and

and  are both zero, by the same argument we had for

are both zero, by the same argument we had for  . Here you can also use the adjunction for reasoning!

. Here you can also use the adjunction for reasoning!

Last words

The nice thing about this setting is that it generalizes to give the following:

Take  a closed subspace in

a closed subspace in  and

and  its open complement, then you have an open embedding

its open complement, then you have an open embedding  and a closed embedding

and a closed embedding  which behave very much like our

which behave very much like our  and

and  from the last examples. It presents the category of sheaves on

from the last examples. It presents the category of sheaves on  as an extension of the sheaves on

as an extension of the sheaves on  by the sheaves on

by the sheaves on  . The same happens for the derived category. The magic word for this situation is "Recollement".

. The same happens for the derived category. The magic word for this situation is "Recollement".

2018-03-26 (26. March 2018)

In 4th line of your "Pullback" section where the notion is defined do you mean to write: "(f^*G)(U):= G(f(U)" where G is a sheaf of abelian groups over Y?

2018-03-26 (26. March 2018)

Corrected, thanks!