Divisorial Jungle

Thursday, November 29th, 2012 | Author: Konrad Voelkel

I'd like to compile a short list of definitions of Weil and Cartier Divisors, Line Bundles and Invertible Sheaves, Class Groups and Picard Groups, Cohomology, (higher) Chow Groups and K-theory for algebraic schemes and their relations. I intentionally omit proofs, but there are some ideas. I couldn't resist to jot down some properties of the objects which are important to me (homotopy invariance, existence of pullbacks and pushforwards).

Let  be an algebraic scheme over a field

be an algebraic scheme over a field  , i.e. a scheme with structural morphism

, i.e. a scheme with structural morphism  of finite type. Whenever any coefficients appear, I chose

of finite type. Whenever any coefficients appear, I chose  , but it might be much more convenient to take

, but it might be much more convenient to take  in applications. It might also be quite convenient to restrict attention to varieties which are smooth over

in applications. It might also be quite convenient to restrict attention to varieties which are smooth over  and assume

and assume  perfect (since these conditions imply regular and normal), but I try to make these assumptions only when necessary. In fact, after writing this, I wish I would have stuck to rational coefficients and smooth schemes.

perfect (since these conditions imply regular and normal), but I try to make these assumptions only when necessary. In fact, after writing this, I wish I would have stuck to rational coefficients and smooth schemes.

Definitions

Cycles and divisors

A  -dimensional cycle of

-dimensional cycle of  is a

is a  -linear combination of

-linear combination of  -dimensional closed subvarieties, i.e. closed immersions from integral algebraic schemes of dimension

-dimensional closed subvarieties, i.e. closed immersions from integral algebraic schemes of dimension  . The group of all

. The group of all  -dimensional cycles is denoted

-dimensional cycles is denoted  . If

. If  is equidimensional, the group of all codimension

is equidimensional, the group of all codimension  cycles is denoted

cycles is denoted  . I will discuss rational equivalence and Chow groups below.

. I will discuss rational equivalence and Chow groups below.

For  equidimensional and regular in codimension

equidimensional and regular in codimension  , a Weil divisor is a

, a Weil divisor is a  -linear combination of codimension

-linear combination of codimension  subvarieties (which are also called prime divisors). A Weil divisor is called effective if the coefficients of the prime divisors are non-negative. To a non-zero rational function

subvarieties (which are also called prime divisors). A Weil divisor is called effective if the coefficients of the prime divisors are non-negative. To a non-zero rational function  one can associate a Weil divisor

one can associate a Weil divisor ![(f) := \sum_Y v_Y(f)[Y]](http://www.konradvoelkel.com/wp-content/plugins/latex/cache/tex_934de3af08cd44a7cbc877f65c2fc95f.gif) , where the sum runs over all prime divisors. Weil Divisors of the form

, where the sum runs over all prime divisors. Weil Divisors of the form  are called principal divisors. The group

are called principal divisors. The group  of divisors modulo principal divisors is called the divisor class group. I will discuss the relation with Chow groups below.

of divisors modulo principal divisors is called the divisor class group. I will discuss the relation with Chow groups below.

A Cartier Divisor is a global section of  , where

, where  is the sheaf of rational functions on

is the sheaf of rational functions on  . A Cartier divisor is called principal divisor if it is in the image of the quotient map from

. A Cartier divisor is called principal divisor if it is in the image of the quotient map from  , i.e. if it can be represented by a global non-zero rational function. The group

, i.e. if it can be represented by a global non-zero rational function. The group  of Cartier divisors modulo principal divisors is called Cartier class group. I will discuss the relation with cohomology below.

of Cartier divisors modulo principal divisors is called Cartier class group. I will discuss the relation with cohomology below.

Invertible sheaves and bundles

An invertible sheaf is a coherent  -module sheaf which is locally free of rank

-module sheaf which is locally free of rank  , i.e. an invertible sheaf

, i.e. an invertible sheaf  is locally isomorphic to

is locally isomorphic to  . For an invertible sheaf

. For an invertible sheaf  the dual

the dual  -module

-module  is a

is a  -inverse via the evaluation isomorphism

-inverse via the evaluation isomorphism  .

.

An algebraic line bundle is an algebraic vector bundle of rank  , i.e. a morphism of schemes

, i.e. a morphism of schemes  with zero section

with zero section  , scalar multiplication morphism

, scalar multiplication morphism  and vector addition morphism

and vector addition morphism  that turn each fiber into a

that turn each fiber into a  -vector space of dimension

-vector space of dimension  , and there exists a Zariski-covering of

, and there exists a Zariski-covering of  and a local trivialization of

and a local trivialization of  such that the corresponding glueing morphisms are

such that the corresponding glueing morphisms are  -linear in each fiber. From a general argument identifying locally free

-linear in each fiber. From a general argument identifying locally free  -modules as sheaves of sections of algebraic vector bundles (which gives an equivalence of categories), algebraic line bundles are equivalent to invertible sheaves. The group of all line bundles modulo isomorphism (with group structure from

-modules as sheaves of sections of algebraic vector bundles (which gives an equivalence of categories), algebraic line bundles are equivalent to invertible sheaves. The group of all line bundles modulo isomorphism (with group structure from  ) is called Picard group

) is called Picard group  .

.

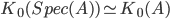

Definitions of some fancy objects

The  -th K-group

-th K-group  of a ring

of a ring  is the Grothendieck ring of projective modules, i.e. the group of isomorphism classes of projective modules modulo the relation identifying a module

is the Grothendieck ring of projective modules, i.e. the group of isomorphism classes of projective modules modulo the relation identifying a module  with

with  if there exists a short exact sequence

if there exists a short exact sequence  (which doesn't necessarily split). The

(which doesn't necessarily split). The  -th K-group

-th K-group  is the Grothendieck ring of algebraic vector bundles. Since projective modules over a ring are, as category, equivalent to vector bundles over its spectrum,

is the Grothendieck ring of algebraic vector bundles. Since projective modules over a ring are, as category, equivalent to vector bundles over its spectrum,  . There are various isomorphic definitions of higher algebraic K-theory of a scheme, but I won't write any of these down. For a ring

. There are various isomorphic definitions of higher algebraic K-theory of a scheme, but I won't write any of these down. For a ring  one can take

one can take  . There is a filtration on

. There is a filtration on  called the Adams filtration, or

called the Adams filtration, or  -filtration (coming from the

-filtration (coming from the  -ring structure), with weight-

-ring structure), with weight- -subspace of

-subspace of  just

just  .

.

For  equidimensional and smooth over

equidimensional and smooth over  , write

, write  for

for  -linear combinations of codimension

-linear combinations of codimension  closed subvarieties of

closed subvarieties of  which intersect all faces

which intersect all faces  (for

(for  ) properly, where

) properly, where ![\Delta^m := Spec(k[t_0,\dots,t_m]/\sum t_i-1)](http://www.konradvoelkel.com/wp-content/plugins/latex/cache/tex_6f42b59810d321fa940b30585322de79.gif) is the affine standard simplex. These fit together to form a simplicial abelian group

is the affine standard simplex. These fit together to form a simplicial abelian group  (with respect to intersection product) and the homotopy groups

(with respect to intersection product) and the homotopy groups  are called higher Chow groups. Obviously,

are called higher Chow groups. Obviously,  .

.

Motivic cohomology are certain Ext-groups in Voevodsky's category of mixed motives (one can take that as definition): ![H^{p,q}(X) = Hom_{DM^{eff}_{Nis}}(\mathbb{Z}_{tr}(X),\mathbb{Z}_{tr}(p)[q])](http://www.konradvoelkel.com/wp-content/plugins/latex/cache/tex_e19e884b02b0fb65df2674664d2c27d8.gif) , where

, where  is the presheaf with transfers associated to

is the presheaf with transfers associated to  .

.

Some properties

After looking at the comparison theorems below, the properties noted here become a lot nicer on smooth schemes, by using the comparisons to get more pullback/pushforward homomorphisms.

Pullbacks

- Cycles can be pulled back along flat morphisms of constant relative dimension, which preserves codimension, rational equivalence and is compatible with the intersection product. The same holds for Weil divisors. There is also flat pullback for higher Chow groups.

- Cartier divisors can be pulled back along any map whose image is not contained in the support of the divisor. By taking a linearly equivalent Cartier divisor, if necessary, one may always pull back the class of a Cartier divisor (on an integral scheme).

- Bundles can be pulled back to bundles along arbitrary morphisms and isomorphic bundles pull back to isomorphic bundles, hence there is a pullback on the Picard group. This generalizes to algebraic K-Theory.

- On sheaf cohomology one has arbitrary pullbacks (sheaf cohomology is a contravariant functor, after all) and the same is true for motivic cohomology.

Pushforwards

- Cycles can be pushed forward along proper morphisms, which preserves dimension and rational equivalence. Since Weil divisors are codimension 1 cycles, they admit proper pushforward only along maps of relative dimension

. There is the degree map, which is just pushforward along the structural morphism

. There is the degree map, which is just pushforward along the structural morphism  . I don't know whether higher Chow groups also have proper pushforward... do you?

. I don't know whether higher Chow groups also have proper pushforward... do you? - I don't know if there is any kind of general pushforward for Cartier divisors or classes thereof.

Bundles can be pushed forward (in the sense of pushforward of sheaves that yields a bundle again) along finite flat morphisms, and there are more morphisms whose pushforward is a vector bundle again. I don't know if there is a nice criterion for which kind of morphism allows pushforward in K-Theory. - For cohomology, pushforwards of sheaves exist in general, but you don't get a pushforward morphism on the cohomology in general. If you take a proper map which is in some sense oriented, then one gets pushforwards on ordinary (singular) cohomology, which look like integration over the fiber in the de Rham picture. I don't know what the general statement for motivic cohomology looks like... do you?

Homotopy invariance

- Chow groups have homotopy invariance, i.e.

, where the isomorphism is induced by pullback along the projection

, where the isomorphism is induced by pullback along the projection  . In particular, the Weil divisor class group has homotopy invariance. Even the higher Chow groups are homotopy invariant, i.e.

. In particular, the Weil divisor class group has homotopy invariance. Even the higher Chow groups are homotopy invariant, i.e.  .

. - The Cartier class group is not homotopy invariant in general, but I don't know good examples.

- The Picard group (and the K-Theory) are homotopy invariant on regular schemes (but I don't know counter-examples in general).

- Sheaf cohomology is not homotopy-invariant in general, but if you take a locally constant sheaf as coefficients, it is. However, in this article, coefficients

are most relevant, and there we don't have homotopy invariance. Motivic cohomology, on the other hand, is homotopy invariant (by construction).

are most relevant, and there we don't have homotopy invariance. Motivic cohomology, on the other hand, is homotopy invariant (by construction).

Comparisons

As far as I can see, all these comparisons are compatible with pullbacks (as far as they exist). For pushforwards, the precise relationship between the Chern character and pushforwards is called Grothendieck-Riemann-Roch theorem.

Weil divisor class group and Chow group of codimension 1 cycles

The usual definition of rational equivalence (that shows up in the definition of the Chow group as in the book of Y.André on motives) looks rather different from the usual definition of linear equivalence (that shows up in the definition of the Weil divisor class group). Linear equivalence is just equality modulo adding principal divisors.

Rational equivalence of two cycles  of codimension

of codimension  in

in  is the existence of a cycle

is the existence of a cycle  of codimension

of codimension  in

in  such that the projection

such that the projection  to

to  is dominant, and

is dominant, and  .

.

These two equivalence relations on codimension-1 cycles agree. From linear equivalence you can easily cook up a  joining the two divisors, but the other direction is tricky. One has to relate the pushforward in the latter definition to the former. The crucial technical result (Proposition 1.4b in Fulton's book on intersection theory) states that for

joining the two divisors, but the other direction is tricky. One has to relate the pushforward in the latter definition to the former. The crucial technical result (Proposition 1.4b in Fulton's book on intersection theory) states that for  a proper surjective morphism of varieties of the same dimension and

a proper surjective morphism of varieties of the same dimension and  a non-zero rational function,

a non-zero rational function, ![p_\ast[div(f)] = [div(N(f))]](http://www.konradvoelkel.com/wp-content/plugins/latex/cache/tex_72f2d01d8d3bf6a2e573d5078d670461.gif) , where

, where  is the norm of the field extension

is the norm of the field extension  . This is applied in the situation where we have

. This is applied in the situation where we have  as in the definition of rational equivalence, but

as in the definition of rational equivalence, but  consists of just a subvariety

consists of just a subvariety  (the general case is done by extending linearly), so there is a morphism

(the general case is done by extending linearly), so there is a morphism  which is induced by the projection

which is induced by the projection  (so,

(so,  determines a rational function

determines a rational function  ) and the other projection

) and the other projection  induces morphisms

induces morphisms  from the scheme-theoretic fiber

from the scheme-theoretic fiber  for any rational point

for any rational point  , which are isomorphisms onto some subscheme we want to call

, which are isomorphisms onto some subscheme we want to call  . Then one has

. Then one has ![[f^{-1}(0)] - [f^{-1}(1)] = [div(f)]](http://www.konradvoelkel.com/wp-content/plugins/latex/cache/tex_9b161e7eca6bb137a5a6f914bab6e782.gif) , hence

, hence ![[V(0)] - [V(\infty)] = p_\ast[div(f)] = [N(div(f))]](http://www.konradvoelkel.com/wp-content/plugins/latex/cache/tex_75ff12ef5a37f54f9dcbbb6cf74ad9ac.gif) , which is linearly equivalent to

, which is linearly equivalent to  (since it's a principal divisor).

(since it's a principal divisor).

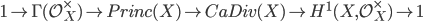

Cartier class group and cohomology:

The short exact sequence of sheaves  yields a long exact cohomology sequence which reads

yields a long exact cohomology sequence which reads  and identifies

and identifies  .

.

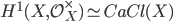

Line bundles and cohomology:

Given a line bundle  one can take any local trivialization

one can take any local trivialization  over an open cover

over an open cover  with patching data

with patching data  and these patching data

and these patching data  form a Cech 1-cocycle over

form a Cech 1-cocycle over  with values in

with values in  , thus a class in Cech cohomology

, thus a class in Cech cohomology  . In the limit, one gets a class in

. In the limit, one gets a class in  , thus from general nonsense a class in the sheaf cohomology group

, thus from general nonsense a class in the sheaf cohomology group  . Different trivializations yield cohomologous cocycles, hence the same Cech classes.

. Different trivializations yield cohomologous cocycles, hence the same Cech classes.

It also works the other way around: Take such a cohomology class, represent it by a Cech 1-cocycle over some open cover  (which has to be fine enough) and write down the bundle patched together from trivial bundles via the patching data. Taking a different 1-cocycle in the same class (or a different open cover) yields an isomorphic bundle, hence

(which has to be fine enough) and write down the bundle patched together from trivial bundles via the patching data. Taking a different 1-cocycle in the same class (or a different open cover) yields an isomorphic bundle, hence  .

.

Cartier divisors and line bundles:

For each Cartier divisor  we can choose an open affine cover

we can choose an open affine cover  such that

such that  is represented by sections

is represented by sections  of

of  over

over  . Then we define a line bundle

. Then we define a line bundle  as the sub-

as the sub- -module of

-module of  generated by the

generated by the  over

over  . This gives a monomorphism

. This gives a monomorphism  .

.

To any line bundle  with embedding

with embedding  we can associate a Cartier divisor

we can associate a Cartier divisor  such that

such that  , by taking

, by taking  to be the inverse of a local generator of

to be the inverse of a local generator of  over

over  (where the

(where the  have to be a trivializing cover). This is obviously an inverse to the other construction.

have to be a trivializing cover). This is obviously an inverse to the other construction.

If  is integral,

is integral,  , a constant sheaf, and then we can embed every line bundle in

, a constant sheaf, and then we can embed every line bundle in  by

by  , since

, since  is locally constant, hence constant. Therefore, on

is locally constant, hence constant. Therefore, on  integral,

integral,  .

.

Compatibility of the isomorphisms so far:

The isomorphism class of line bundles we attached to a Cartier class turns out to be the same isomorphism class of line bundles specified by the cohomological data given by the Cartier class, which one can see explicitly by taking a Cartier divisor  and assign the isomorphism class of line bundles specified by the patching data

and assign the isomorphism class of line bundles specified by the patching data  .

.

Cartier divisors and Weil divisors:

On  integral, separated, noetherian and regular in codimension

integral, separated, noetherian and regular in codimension  , Cartier divisors can be mapped to locally principal Weil divisors, by representing the Cartier divisor over a cover

, Cartier divisors can be mapped to locally principal Weil divisors, by representing the Cartier divisor over a cover  as some

as some  and for each prime divisor

and for each prime divisor  taking some index

taking some index  such that

such that  , then

, then  is well-defined (doesn't depend on

is well-defined (doesn't depend on  ) and

) and  is a locally principal Weil divisor.

is a locally principal Weil divisor.

If  is furthermore normal, each locally principal Weil divisor

is furthermore normal, each locally principal Weil divisor  comes from a Cartier divisor, since for each point

comes from a Cartier divisor, since for each point  we can take the restriction

we can take the restriction  , a divisor on

, a divisor on  , and

, and  is a UFD, so

is a UFD, so  is a principal divisor,

is a principal divisor,  and

and  defines a divisor on

defines a divisor on  which restricts to

which restricts to  as well, so agrees on an open neighborhood

as well, so agrees on an open neighborhood  with

with  ; the various

; the various  give a Cartier divisor, since

give a Cartier divisor, since  is normal, so on any open

is normal, so on any open  with

with  inducing the same Weil principal divisor,

inducing the same Weil principal divisor,  is a section of

is a section of  .

.

If  is furthermore locally factorial, every Weil divisor is locally principal, so

is furthermore locally factorial, every Weil divisor is locally principal, so  . Since principal divisors agree,

. Since principal divisors agree,  . In particular this holds for smooth

. In particular this holds for smooth  .

.

The map from an isomorphism class of line bundles to a linear equivalence class of Cartier divisors to a rational equivalence class of Weil divisors is also called  , the first Chern class. Note how one has such a map

, the first Chern class. Note how one has such a map  even if

even if  and

and  are only monomorphisms. This map is called

are only monomorphisms. This map is called  , the first Chern class of a line bundle.

, the first Chern class of a line bundle.

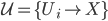

I want to summarize, for  smooth over

smooth over  , we have

, we have

Comparison of fancy objects

Comparison of Chow groups and K-Theory in general, for  smooth over

smooth over  :

:

where the  indicates the

indicates the  -filtration.

-filtration.

This is the Chern character, which you can build by identifying  with the

with the  -group of coherent sheaves on

-group of coherent sheaves on  (there smoothness is used), and then one can take a resolution of a coherent sheaf by vector bundles (on a stratification) and define ordinary chern classes for vector bundles via a splitting principle and

(there smoothness is used), and then one can take a resolution of a coherent sheaf by vector bundles (on a stratification) and define ordinary chern classes for vector bundles via a splitting principle and  .

.

This generalizes to higher Chow groups and higher K-Theory (but I don't know who proved that):

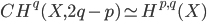

Voevodsky proved that these are strongly related to motivic cohomology:

for

for  smooth over

smooth over  and

and  a perfect field, where the map is the so-called motivic cycle class map.

a perfect field, where the map is the so-called motivic cycle class map.

We recover the comparison of divisors with line bundles and cohomology (but now with rational coefficients):

where  is just

is just  and

and  and

and  .

.

I don't know how to prove that stuff :-) but I hope I'll learn that some day.